Introduction

The NZ charities register currently has over 6,000 charities that operate in the “sport / recreation” sector. Approximately 1,700 of these charities, representing 6% of all NZ registered charities, have recorded “sport / recreation” as their main sector of operation. They range from golf clubs (with fees exceeding $5,000) to bridge and chess clubs, sports stadiums and marinas. This approach differs markedly from the charity regulator across the Tasman, which has only registered 175 charities with sports as a main activity.

The NZ Charities Act 2005 was amended in 2012 to clarify

that although the promotion of amateur sport is not a charitable object of

itself, it may be charitable if it is the means by which another charitable

purpose is pursued. The regulator subsequently published guidance “When are sport and

recreation organisations charitable?” To meet the public benefit test, it explained

that sporting charities must be directed towards amateur sports and not to

professional or elite sporting; it states that a sports club must not have

exclusive membership or high fees, the sport must not be excessively dangerous

and the club must not focus on social activities. The guidance also states that promotion of

sport in and of itself is not a charitable purpose – it must be the means by

which a charitable purpose is pursued, for example to advance education or

promote health.

One of the hottest sporting charity topics in NZ at

present involves governing sports bodies.

As recently as September 2015 the charities regulator published its decision to deregister the

NZ Rowing Association Incorporated. The Charities Registration Board acknowledged

that NZ Rowing had purposes to promote rowing as a means of promoting public

health and advancing education. However

it also found it had a purpose of promoting rowing as an end in itself (ie it

was a sports promotor / governing body) and it had a purpose to promote success

in rowing at an elite level, both being non-charitable purposes. The reasons for this decision were consistent

with the reasons for deregistering Swimming NZ

Incorporated in

September 2014.

It is worth noting that many sports clubs in NZ are

exempt from income tax under a specific amateur sports body provision of the

Income Tax Act 2007. For these clubs,

registration as a charity will not bring additional income tax exemption

benefits. Section CW 46 of the Income

Tax Act 2007

provides an income tax exemption if clubs are established mainly to promote any

amateur game or sport, for the recreation or entertainment of the general

public. Consequently there are many

incorporated sports clubs that have decided not to register as charities and

instead file annual incorporated society returns with the Companies Office, which

are publicly available on the Companies Office Other

Registers

webpage. This means analysis of sports

club information on the Charities register will not provide a comprehensive

picture of all sports clubs in NZ.

Despite the abovementioned limitation, the purpose

of this paper is to sift through data on the Charities Register and identify

lessons that may be useful for sports organisations that are, have been or may

be registered charities.

Summary

Summary

Based

on my analysis of information contained on the NZ and Australian charities

registers, here are eight insights about sporting charities:

1. What types of sports

groups register as charities? Although you might have expected rugby and

netball clubs to dominate the types of sports on the NZ charity register, in

fact golf clubs top the list, followed by tennis clubs, rugby, surf lifesaving,

cricket and cycling. However the

assortment of sports charities is very wide, with well over 40 types of sports

appearing such as bridge, chess, skiing, yachting, equestrian, croquet, water

polo, judo and marching. There are a

number of stadiums and even marinas.

2. Is the number of sports

charities increasing or decreasing? Just over 2,000 charities with

sport/recreation as their main sector have been registered since 2007 and 325

(16%) of these have been deregistered.

One third of these deregistrations were voluntary and two thirds were

initiated by the regulator, almost all because of failure to file annual

returns. 2015 (January to October) is

the first year the number of sports charities declined overall, with 62 new

registrations but 88 deregistrations.

3. What is the preferred

legal structure for a sports charity?

64% (1,118) of sports charities are incorporated societies, which is the preferred

structure for sports charities. 30%

(523) are trusts, 1% (22) are limited liability companies and 5% (94) are

unincorporated or do not specify their structure.

4. How do sports charities

earn most of their money? 55%

of sports charities earned trading or service provision income in 2014, which

brought in $131m. This makes up one

third of sports charity income by dollar value. Sales of wine, food and sports clothing is common for small, medium and

large sports charities. So is renting

out venues, hiring gear, and charging for advertising. Service provision includes income from gate

takings, rep team fees, league fees and tournament fees.

5. Are donations from the

public very common for sports charities?

The raw data suggests that

in 2014 just over half (51%) of sports charities received donations, which

brought in $19m. If this was accurate,

it would confirm the benefit of donee status awarded to most charities, where

sports clubs can provide donors with donation tax credit receipts. However on closer examination most of this

money was from government and non-government grants that the charities had

mistakenly classified as donations. The

grant sources were what you would expect, for example various community trusts,

the Lion Foundation, First Sovereign Trust, NZ

Lotteries, Councils and Pub Charity.

Donations from individuals or businesses were much harder to find. Three themes that stood out were: (i) people

would donate for recreation reserves and parks; (ii) they would donate to a

charity they settled themselves; and (iii) they would donate if the sports charity

was linked to another organisation they were involved with (for example, to a

charitable foundation that funded a sports club).

6. Many sports clubs have decided

not to register as a charity – so is it worth it? Using

golf clubs as an example, only one quarter of NZ’s 384 golf clubs that are incorporated societies

decided to register as charities. The

rest did not. Instead they continue to

file annual incorporated society returns with the Companies Office and still

benefit from the amateur sport tax exemption under section CW 46 of the Income

Tax Act. They also avoid the red tape of

having to inform two regulators – DIA and the Companies Office – when members

or governing documents change, and they will not be required to apply the new

accounting standards for charities. The

lesson for all sports charities is therefore to make sure registration as a

charity brings tangible benefits (such as access to new sources of funding). If it doesn’t, then registration as a charity

may not be worthwhile.

7. Is the NZ regulator’s approach to sports groups different to the Australian regulator? Like NZ, Australia does not recognise amateur sport to be a charitable object in itself - an organisation’s sporting activities must be part of achieving a recognised charitable purpose in order for the organisation to be charitable. Despite this similarity, there is a marked difference between NZ and Australia in respect of registering sports bodies as charities. Very few (less than half a percent) of Australian registered charities record sport as a main activity, compared to 6% in NZ. And almost all of those sports groups in Australia are directly involved with sickness or disability, which aligns with guidance published by the Australian Tax Office about the limited circumstances when a sports organisation will be charitable. This is far different to NZ which has registered many ordinary sports clubs. The conclusions I have drawn are that more sports clubs in NZ than Australia have identified benefits from being a charity (for example, if certain funders will only provide money to registered charities) and therefore more applied to register, and / or the NZ regulator has taken a more liberal interpretation about whether sporting activities achieve other charitable purposes.

8. Do most sports charities pay staff or just rely on volunteers? Just over half of the sports charities in 2014 had no paid staff and relied solely on volunteers. If you are a typical charity in that category you will probably have about 11 volunteers and a gross income around $60,000. However the larger you get the more likely you are to have at least part time employees – one third of sports charities incurred salary expenses in 2014. If you only have paid staff and no volunteers at all you are more likely to be a governing body or a significant charity such as a sports stadium, with income averaging $1.7 million.

7. Is the NZ regulator’s approach to sports groups different to the Australian regulator? Like NZ, Australia does not recognise amateur sport to be a charitable object in itself - an organisation’s sporting activities must be part of achieving a recognised charitable purpose in order for the organisation to be charitable. Despite this similarity, there is a marked difference between NZ and Australia in respect of registering sports bodies as charities. Very few (less than half a percent) of Australian registered charities record sport as a main activity, compared to 6% in NZ. And almost all of those sports groups in Australia are directly involved with sickness or disability, which aligns with guidance published by the Australian Tax Office about the limited circumstances when a sports organisation will be charitable. This is far different to NZ which has registered many ordinary sports clubs. The conclusions I have drawn are that more sports clubs in NZ than Australia have identified benefits from being a charity (for example, if certain funders will only provide money to registered charities) and therefore more applied to register, and / or the NZ regulator has taken a more liberal interpretation about whether sporting activities achieve other charitable purposes.

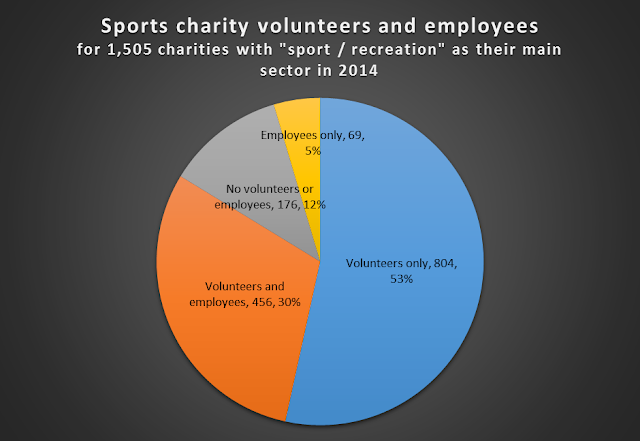

8. Do most sports charities pay staff or just rely on volunteers? Just over half of the sports charities in 2014 had no paid staff and relied solely on volunteers. If you are a typical charity in that category you will probably have about 11 volunteers and a gross income around $60,000. However the larger you get the more likely you are to have at least part time employees – one third of sports charities incurred salary expenses in 2014. If you only have paid staff and no volunteers at all you are more likely to be a governing body or a significant charity such as a sports stadium, with income averaging $1.7 million.

The

details

1. Registration and income trends

1. Registration and income trends

The total number of registered sports charities that have ‘sport/recreation’ as their main sector has increased every year since 2009, as shown in Graph 1 below. However, there has been a reduction in the number of returns filed in 2014, largely due to an increase in 2014 delinquent filers.

The trend in

gross income reported by sports charities has been consistent with the trend in

volume of sports charities that have filed returns over the last six

years. It has grown from $268m in 2009

to a high of $437m in 2012, and fallen to $415m in 2014.

Table A shows a

year-by-year breakdown of sports charities registered and deregistered, distinguishing

the deregistered charities by voluntary deregistrations and deregistrations

initiated by the regulator.

From 2007 to 2015 the

regulator registered 2,082 charities with sport / recreation as the main

sector.

Over the same period, 16%

or 325 have been deregistered, leaving a net total of 1,757 currently on the

register (as at October 2015). From

2007, an average of one third of deregistrations were voluntary and two thirds

were initiated by the regulator, the latter being largely due to failure to

file the annual return. The number of

regulator deregistrations increased significantly in 2015, which appears to be

due to an increased focus on deregistering charities that have not filed their

annual returns, rather than a focus on whether sports charities have a

charitable purpose. So far this 2015

calendar year, 84% of sports charity deregistrations were initiated by the

regulator.

Table A

2. Types of sports clubs on the register

Sports charities are not

required to categorise their sporting activity on the NZ Charities Register so

for the purpose of this paper I filtered the names of the charities that have

recorded “sport / recreation” as a sector they operate in, looking for common

sports words. The result in Table B,

showing the 30 most common sports charities, is not comprehensive, but gives an

indication of the types of sporting activity that has been registered.

Table B

No. of charities

|

Word in Name

|

No. of charities

|

Word in Name

|

85

|

Golf

|

20

|

Squash (excluding squash and tennis, which are included in tennis)

|

80

|

Tennis

|

17

|

Skiing

|

76

|

Rugby

|

17

|

Tramping

|

73

|

Surf Life Saving

|

16

|

Badminton

|

53

|

Cricket

|

15

|

Canoe

|

51

|

Biking / Cycling

|

14

|

Yacht

|

51

|

Swimming

|

11

|

Alpine (excluding ski)

|

50

|

Football / Soccer (excluding rugby football, which are included under

Rugby)

|

11

|

Equestrian

|

47

|

Bowling

|

10

|

Baseball / Softball

|

45

|

Hockey

|

10

|

Croquet (excluding croquet and bowling, which are included in bowling)

|

35

|

Rowing

|

10

|

Deerstalkers

|

33

|

Netball

|

8

|

Boxing

|

33

|

Bridge

|

8

|

Dancing

|

30

|

Gym sports / Gymnastics

|

7

|

Harrier

|

28

|

Basketball

|

7

|

Chess

|

In addition to these

sport-specific charities, there are 16 charities with “stadium” in their names,

and 4 with “marina” (Orakei, Whangarei, Tutukaka and Whangaroa). Many of the remaining charities could be

associated more with recreation rather than sport per se (for example 232 had

“centre” in their name, ranging from recreation and craft centres to seniors

centres), or a range of sports (there were a large number of trusts and

organisation names that were solely or primarily sports related, but the name

gave no indication of the sports involved).

3.

Sources of income

The source of income

reported by charities with ‘sport/recreation’ as their main sector is dominated

by “income from service provision / trading operations”, with an average of one

third of gross income from that source over the last six years. This is followed by income from “government

grants / contracts” (19%), “all other grants and sponsorship” (19%) and

“membership fees” (11%). Donations to

sport/recreation groups accounted for only 4% of gross income. Not surprisingly, bequests were the least

common source of income, with only 20 charities out of 1,505 reporting bequest

income in 2014. The six-year average

breakdown is shown in Graph 2.

4. The “top 10” charities (based on income)

As shown in Table C, below, three

sport/recreation charities reported gross income of more than $10m in 2014 –

the Auckland YMCA, Wellington Regional Stadium Trust and The Home of Cycling

Charitable Trust. The charity ranked

fourth on the list, the NZ Rowing Association, was deregistered in September

2015 on the basis that it had non-charitable purposes (ie sports promotion at

an elite level). Wellington Zoo featured

in the top 10 because it classified its main sector as recreation (Auckland Zoo

did not appear because it classified its main sector as “environment /

conservation”).

Table C

Top 10 Sport/Recreation

Charities ranked by 2014 Gross Income

|

$m

|

|

1

|

Young Men's Christian

Association Of Auckland Incorporated

|

19

|

2

|

The Wellington Regional

Stadium Trust Incorporated

|

16

|

3

|

The Home Of Cycling

Charitable Trust

|

11

|

4

|

New Zealand Rowing

Association Incorporated

|

9

|

5

|

Southland Indoor Leisure

Centre Charitable Trust

|

8

|

6

|

Auckland Sport

|

8

|

7

|

Millennium Institute of

Sport and Health

|

7

|

8

|

Tennis Auckland Region

Incorporated

|

6

|

9

|

Sport Northland

|

6

|

10

|

Wellington Zoo Trust

|

6

|

5. Sources of income from “Service Provision

/ Trading Operations”

825 out of 1,505 sport/recreation charities

(55%) reported income from “service provision / trading operations” in 2014,

which was the largest source of income by dollar value ($131m). Sports stadiums ranked high on the list with

three (Wellington, Christchurch and Marlborough) in the top 10, as shown in

Table D.

Table D

Top 10 Sport/Recreation

Charities ranked by 2014 Service Provision / Trading Income

|

$m

|

|

1

|

The Wellington Regional

Stadium Trust Incorporated

|

16

|

2

|

Young Men's Christian

Association Of Auckland Incorporated

|

11

|

3

|

The Manukau Counties

Community Facilities Charitable Trust

|

6

|

4

|

Mana Community Grants

Foundation

|

5

|

5

|

Millennium Institute of

Sport and Health

|

3

|

6

|

Christchurch Stadium

Trust

|

3

|

7

|

Wellington Zoo Trust

|

3

|

8

|

Remuera Golf Club

Incorporated

|

2

|

9

|

New Zealand Water Polo

Association Incorporated

|

2

|

10

|

Marlborough Stadium Trust

|

2

|

To get an insight into

the nature of the service provision / trading income of small/medium charities,

I reviewed the financial accounts for 30 charities which disclosed this type of

income in 2014, ranging from $5,000 to $200,000. Here is what I found:

·

Sales of wine, food and sports clothing is a common

way for sports charities to make money.

At the small end some charities buy wine and sell it, they take a fee

from food vendors, or members will volunteer for bar work and donate proceeds

to the charity. They also sell uniforms,

sports gear or t-shirts to members. As they get bigger, charities run their own

bars, canteens and clothing pro-shops.

·

Renting or hiring space or gear is a common income

source. Smaller charities rent their

rooms when they are not using them; a bowling club hired out its turf

maintenance gear to other clubs. Bigger

charities hire out their gyms, halls or turf.

Venue hire is a source of income for the stadiums.

·

Advertising income can be lucrative for some

charities, ranging from signage to website placement.

·

Small charities recorded income from the sale of

calendars, cards and stamps.

·

Charities with a sport oversight/promotion role

tended to earn trading income from gate takings, rep team fees league fees and

tournament fees.

·

The most unusual source of trading income in the

sample was a bowling club recording income from the sale of bonds.

6. Membership fees and donations

Membership fees are often a modest but important source of income for

sports charities. They can also be

problematic if the charities regulator believes they are set so high that an

organisation is exclusive and does not meet the public benefit test. Similarly, problems may occur if a charity

categorises its membership fees as donations and draws the attention of Inland

Revenue, who will want to ensure donation tax credits are not claimed if the

amount paid results in membership benefits. From a practical perspective, deciding whether

an amount received should be classified as a donation or a grant in the charity

regulator’s annual return is clearly also difficult for many charities, with no

consistency in the approach (based on my sample).

906 out of 1,505

sport/recreation charities (60%) reported income from membership fees in 2014,

which brought in $48m. A smaller number,

762 (51%) reported income from donations, which brought in $19m. Golf clubs ranked high on the membership fee list

with three (NZ Golf Incorporated, Remuera Golf Club, Christchurch Golf Club) in

the top 10, as shown in Table E. A foundation linked to the Royal Wellington

Golf Club also made it into the top 10 for donations, as shown in Table F.

Table E

Top 10 Sport/Recreation Charities

ranked by 2014 Membership Fees

|

$m

|

|

1

|

Young Men's Christian

Association Of Auckland Incorporated

|

5

|

2

|

New Zealand Golf Incorporated

|

3

|

3

|

Millennium Institute of

Sport and Health

|

2

|

4

|

Remuera Golf Club Incorporated

|

2

|

5

|

Young Men's Christian Association

Of Taranaki Incorporated

|

2

|

6

|

The Scout Association of

New Zealand

|

1

|

7

|

Tri Star Gymnastic Club

Incorporated

|

0.8

|

8

|

Sport Northland

|

0.7

|

9

|

Christchurch Golf Club Incorporated

|

0.7

|

10

|

Pakuranga Country Club

Incorporated

|

0.7

|

Table F

Top 10 Sport/Recreation

Charities ranked by 2014 Donations

|

$m

|

|

1

|

Southland Indoor Leisure

Centre Charitable Trust

|

4

|

2

|

Tai Shan Foundation

|

4

|

3

|

The Bruce Pulman Park

Trust

|

3

|

4

|

RWGC Golf Foundation

|

1

|

5

|

Sport Bay Of Plenty

Charitable Trust Board Incorporated

|

1

|

6

|

SPIRIT OF ADVENTURE TRUST

|

1

|

7

|

Akarana Marine Sports

Charitable Trust

|

1

|

8

|

Bay Oval Trust

|

0.3

|

9

|

The Te Mata Park Trust

Board

|

0.2

|

10

|

Fiordland Community

Swimming Pool Association Incorporated

|

0.2

|

·

The Southland Indoor Leisure Centre financial

statements show the donation income is actually the total of six grants from

various councils. It appears to be a

misclassification and would have been more appropriately classified as

government grants.

·

The Tai Shan Foundation received its donation of

$3,525,000 from its trustee Frank Pearson, who also donated $1.9m in 2013. The foundation appears to have been set up

by Mr Pearson, an investment banker and the former head of BNZ, in 1985 with

the purpose of encouraging and promoting social equity and harmony in NZ. The charity has accumulated funds of $7m and

in 2014 made donations itself of $63,410.

·

The Bruce Pulman Park Trust financial accounts

record the $3,009,037 figure as “Donations and Grants Received” and disclosed

all four payers – Manukau Counties Community Facilities Charitable Trust, ASB

Community Trust, Counties Manukau Sports Foundation and Probus.

·

The RWGC

Golf Foundation provided a one page

extract of its 2014 financial accounts and an audit report. It recorded 2014 donation income of $839,000

($1.2m in 2013) which, according to past accounts, is all received from members

of the Royal

Wellington Golf Club. The accounts show that almost all of the

charity’s assets ($3,933,000 out of $3,951,000) are represented by a loan to

the Royal Wellington Golf Club. The

accounts state the objects of the Trust are to promote the game of golf with

particular reference to the golf courses operated by the Royal Wellington Golf

Club. The latter is not a registered

charity which may be because it would not qualify due to its relatively high fees

and exclusive nature (the

website shows its annual fee for full playing members is

$2,250). This structure would appear to

be a way for sports club members to claim donation tax credits for “donations” to

a foundation that ultimately funds their own non-charitable sports clubs.

·

Sport Bay of Plenty Charitable Trust disclosed its

$741,902 donations were made by six charitable organisations – Rotorua Energy

Charitable Trust, NZ Community Trust, BayTrust, Lion Foundation, First

Sovereign and Tauranga Energy Consumer Trust.

·

The Spirit of Adventure Trust did not disclose the

source of its $517,372 donations in its 2014 financial report. However it has a full list of its major and

supporting contributors (without amounts) on

its website which include the Ministry of Youth Development, NZ

Community Trust, Pub Charity, The Lion Foundation, and the Community

Organisation Grants Scheme.

·

Akarana Marine Sports Charitable trust’s 2014

financial accounts show that its only income was from $499,943 donations. The charity began in late 2012 so is

relatively new and raising funds to build the $12m Hyundai Marine Sports

Centre, as

reported in the media on 22/06/2015. It did not disclose the source of donations

apart from noting $7,643 was from the Royal Akarana Yacht Club, a related party

as the trustees are members of the yacht club’s committee (the club donated

$174,332 the previous year). The Royal Akarana Yacht Club is not a registered charity, however its website says it receives

funding from The Lion Foundation, NZ Community Trusts, Four Winds Foundation

Ltd and the Trillian Trust.

·

The Bay Oval Trust’s purposes are to promote and

facilitate cricket in the Bay of Plenty.

Its financial statements provide names of its 11 donors for $281,688

donations. They are mostly individuals

and private businesses, some of which are explained further in a related party

note. This charity also reported receiving

grants of $1.4m, which it (correctly) classified as grants rather than

donations. It listed their source – NZ Community Trust, Lion Foundation, First

Sovereign Trust, NZ Racing Board, NZ Lotteries, TECT, Tauranga City Council and

Pub Charity.

·

The Te Mata Park Trust Board disclosed the names of

five donors, with the sixth donor of $25,000 being anonymous. Two donors were

linked to tramping (the charity owns 95 hectares of land in Hawke’s Bay

including Te Mata Peak).

·

The Fiordland Community Swimming Pool Assn disclosed

$214,495 donations but did not provide any further information in its financial

accounts. However, the vice president

was quoted

in the media on 11/10/2013 saying that donations

for the pool’s structural repairs were received from Lotteries, Community Trust

of Southland, Kepler Challenge, Te Anau Community Board and Southland District

Council.

7. A close look at golf clubs

In 2014, 65 golf

charities filed annual returns with the regulator (there are approximately 85

golf charities registered in total). The

number which filed returns is approximately the same number of Inland Revenue approved

donee organisations with 'golf' in their name (64)). These charities controlled assets valued at

$136m and recorded gross income of $27m which included membership fees of

$12m. They recorded 658 volunteers, 156

full time and 96 part time employees (total salaries/wages were $8m).

The 14 most significant

golf charities, either by virtue of their asset size, gross income size, or

membership income, are listed in Table G below, along with an indication of

their annual membership fee if available on their website. It would be interesting to know whether the

regulator has considered if any of these fees are significantly “high” to fail

the public benefit test.

Table G

As mentioned earlier in

this paper, amateur sports clubs such as golf clubs do not need to register as

a charity to obtain an income tax exemption.

The Incorporated Society Register, maintained by the Companies Office, currently

shows 384 active registered golf clubs.

This indicates approximately 300 or three quarters of all golf clubs

made the decision not to register as charities, and instead they only file incorporated

society annual returns with the Companies Office.

8. Volunteers and paid staff

The number of volunteers and employees assisting sports charities in 2014 is shown in Graph 3 below. In total there were 32,517 volunteers, 1,550 full time staff and 2,504 part time staff. 501 of the 1,505 charities (33%) paid salaries which totalled $108 million. The largest salary expense by far was $11 million paid by the YMCA of Auckland, followed by the Wellington Zoo which paid $4 million.

The number of volunteers and employees assisting sports charities in 2014 is shown in Graph 3 below. In total there were 32,517 volunteers, 1,550 full time staff and 2,504 part time staff. 501 of the 1,505 charities (33%) paid salaries which totalled $108 million. The largest salary expense by far was $11 million paid by the YMCA of Auckland, followed by the Wellington Zoo which paid $4 million.

53% of sports charities

relied solely on volunteers, with 11 volunteers being the average for this

group and $63,000 being the average gross income of the charity. Six of these charities

reported having over 100 volunteers – five being football/rugby clubs and the

sixth was the Canterbury Sheep Exhibitors and Breeders A&P Association. In contrast, 75 charities in this group

reported just one volunteer and most had income under $10,000.

12% of sports charities

reported having no employees or volunteers at all. That may be true for the trusts – which

accounted for over half of the 12%.

However one third may just not have answered the question (they received

income so are likely to have drawn on at least some volunteer or paid

resource).

5% of sports charities

relied solely on paid staff, with 5 full time and 5 part time staff being the

average for this group and $1.7m being the average gross income. These charities included stadiums and

governing bodies such as the NZ Rowing Association (now deregistered), NZ Golf,

Basketball NZ, Tennis NZ, The Home of Cycling, Auckland Sport, Sport Southland,

etc.

Graph 3

9. The approach across the Tasman

The Australian Charities

and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) began to regulate charities from 3

December 2012. Approximately 56,000 charity

records were transferred from the Australian Tax Office at that time and from

that point the ACNC began to register new charities. 2,558 new charities were registered in the

year ending 30 June 2015 according to its recent 2015-2018

Strategic Plan. At the time of writing this paper there were

54,185 charities on the register, a reduced number because the ACNC also

revoked registration of charities that no longer operate or did not comply with

their reporting obligations.

The ACNC issued a factsheet

for sporting groups in July 2015 which

explains that generally sporting clubs do not meet the legal meaning of charity

unless the sporting activities are part of achieving a recognised charitable

purpose such as advancing education or social or public welfare. This approach is consistent with the ATO’s

previous interpretation (refer to the ATO’s 2011

Decision Impact Statement for Bicycle Victoria vs Commissioner of Taxation where the Tribunal found that promoting cycling for the purpose of

promoting fitness was a charitable purpose).

The ATO’s

exemption checklist for sporting organisations reiterates that the vast majority

of sporting clubs are not charities. It

cites three examples where sports clubs are charities:

·

a club wholly integrated in a school or university

and furthering its educational aims

·

a club that primarily uses a game or sport to help

rehabilitate the sick, and

·

a club that primarily uses a game or sport to

relieve disability.

In their Annual Information

Statements (AISs), each charity must record the type of activities they

undertook in the previous year. Sport is

an activity category. Based on the 2013

AIS data, 1,434 out of 49,010 charities which filed an AIS conducted sporting activities

(3%). However only 175 charities

identified sport as their main activity (0.4%), far less than the 1,700 (6%)

that identified “sport / recreation” as their main sector in New Zealand. Surf lifesaving clubs accounted for 31 of

these charities. Almost all of the

remainder made it clear that sports were associated with sickness or

disability. For example, Australian

Rules Football for people with intellectual disabilities; running for vision

impaired people; horse riding for disabled people; sports for deaf people;

equestrian for people with disabilities; blind bowlers, dragon boat racing for

cancer sufferers, etc. General sporting

organisations such as golf clubs are not registered charities in Australia.

Similar to New Zealand,

Australian not-for-profit sports clubs are exempt from income tax, as explained

in the ATO’s

exemption checklist for sporting organisations. So there are no income tax

advantages for them to register as charities.

However as the ATO points out, if a sports club qualifies as a charity

it must register as a charity because

it will no longer be eligible for the general sports organisation income tax exemption

(which is not the case in NZ).

If the ACNC registers

charities as a Public Benevolent Institution (PBI) or Health Promotion Charity

(HPC), they will generally receive additional GST, Fringe Benefit Tax and

Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) tax benefits.

Out of the 175 charities with sports as a main activity, approximately

89 are approved PBIs and 6 are approved HPCs.

There may be other reasons for sports clubs to seek charity registration

in Australia, for example the tax office requires some organisations to be

registered charities before approving donations to them to be tax deductible

(ie approving DGR status).

Data references

Data for this paper was extracted from the New

Zealand and Australia charity registers between 13 and 28 October 2015. The Australian data was made available to

data.gov.au on 4 October 2015.

Disclosure

My contract as the Director of Compliance and

Reporting at the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission ended in

August 2015. The above analysis does

not take into account any protected information obtained during my time at the

ACNC. Any errors are mine and opinions

do not represent the views of my previous employers.

Further reference

You can find more data about charities on the following sites:

www.data.gov.au

www.charities.govt.nz

You can also follow my regular data insights about charities on twitter at

https://twitter.com/StuDonaldsonNZ

You can find more data about charities on the following sites:

www.data.gov.au

www.charities.govt.nz

You can also follow my regular data insights about charities on twitter at

https://twitter.com/StuDonaldsonNZ

You

can find more information about NZ sports charity issues at:

Sport NZ: “Charitable registration for sport and recreation

organisations - update December 2014” NZ Law Society: “Is sport charitable any more?” 10 April 2015 (Maria Clarke)

1 comment:

Thankyou Stewart for your thorough analysis of charities with sporting activities. The comparison of the New Zealand register with the Australian register and the observation of the different proportions of "sports" charities was particularly interesting. Australian charities attract additional tax concessions to non charity not-for-profits and thus it seems that there would be incentive to make an application for charity status. The data and the cases indicate a different approach to law and regulation in Australia. The case you cite of Bicycle Victoria illustrates the Australian approach.

As for marinas, it may be that the Preamble to the Statute of Uses 1601 gives some guidance when it refers to the repairs of ports havens and seabanks as charitable purposes.

YMCA has support from the High Court of Australia that it is a religious institution using various activities to advance religion.

Murray Baird

Melbourne Australia

Post a Comment